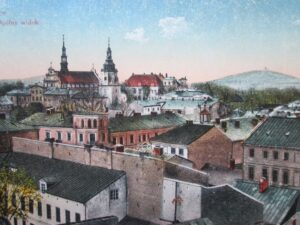

Prior to World War II, there were about eighteen thousand Jews in Kielce. They were rightful and active citizens of the city, which they considered their home. Not many people realised that this was one of the youngest Jewish communities in Poland.

For many years, Jews were prohibited from settling in Kielce. They had lived for hundreds of years in nearby towns, such as Chęciny, Chmielnik, Pińczów, Raków, Wierzbnik, and Ostrowiec but the owners of Kielce, the Krakovian bishops, did not allow Jews to set up permanent residence in the city. This prohibition was finally lifted after the Tsar’s imperial edict on the equality of rights for Jews in 1862.

In 1876, a decision to build a railway line from Dęblin to Dąbrowa Górnicza stimulated an increase in Jewish settlement in Kielce. In 1860, 2640 Jews were living in the city. They were predominantly involved in trade, which was a poorly developed industry in Kielce, and the newly-established companies quickly built up a solid reputation even with Polish clients. It took the townspeople a long while to come to terms with their Jewish competition. The following quarter century was a period of tumultuous development for the city. Kielce’s population had tripled since 1905 and now stood at nearly 30,000. In this period the number of Jews in the city increased four-fold, reaching 10,587.

Jewish traders were present in all areas of trade. Handicrafts were advancing, and cottage industry was undergoing large scale expansion. The period also saw the establishment of industrial plants, which had been absent from Kielce until that time. Above all, there was an abundance of natural resources and wood to be utilized, and the Jews built the foundation for Kielce’s wood and lime industries. Leather tanneries, small soap and candle manufacturers, small accessories producers as well as mills emerged. Kielce also became a city of cobblers.

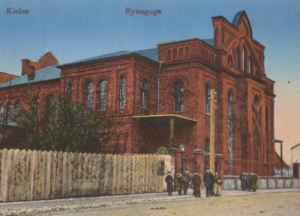

The religious and social lives of Kielce’s Jewish residents were overseen by the synagogue. In 1868, the first rabbi of Kielce district was appointed – Gutman Rapoport, and in 1878 a plot of land was purchased on Warszawska Street to serve as the location for a synagogue.

At this time, members of the intellectual class started pouring into the city and two worlds clashed. One was the world of tradition, represented by Jews from the provinces raised in the age-old tradition. The other was of the world of modernity, represented by those who arrived in Kielce from other cities of the Russian empire. Until the end of the 19th century, the attitudes of Kielce’s Jewish community were governed by tradition and Orthodox law, but the turn of the 20th century saw the emergence of a new generation who were open to the growing ideas of Zionism and socialism. The community of Kielce Jews was for the most part poor. There were barely thirty wealthy families of industrialists and wholesalers, and about one hundred intellectual families lived at a decent level. But the vast majority of Kielce Jews lived very humble lives. Over one hundred families required permanent support from the district, and 1901 saw the establishment of the Society for the Aid of the Mosaic Poor.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Jews of Kielce undertook their construction project of the century – the building of their own synagogue. In 1901, Estera and Mojżesz Pfeffer donated a large square near Nowowarszawska Street as well as 20,000 rubles towards the cost of construction. The synagogue was ceremoniously opened in 1903. At this time, the rabbi in Kielce was Mosze Nachumem Jerozolimski.

After a great fire which destroyed the town of Chęciny in 1905, a significant part of the town’s Jewish population relocated to nearby Kielce. The number of Jews in Kielce increased by seven thousand in the ten years between 1905 and 1915.

Many Hasidic Jews came to Kielce during this time. Reb Chaim Szmuel Horowicz, the great-grandchildren of Zaddik Icchak Horowicz – the Seer of Lublin, one of the foremost representatives of Hasidism in Poland; Reb Motele Twerski, known as Rebbe of Kuzmir (from Kazimierz) the grandson of Mordechaj Motele and great-grandson of Nachman, known as Magidem of Czarnobyl; as well as Reb Chaim Majer Finkler, the brother of Zaddik Hilel of Radoszyc were among those who lived in Kielce.

With the arrival of the new century, the world of religion and tradition began to recede into the past and the new generation took over. They shunned

submissiveness to the authorities and boldly stood up for their rights. A cinema – the first in Kielce – was established, Jewish political parties came into being, and cultural and sport associations were founded. Non-practicing Jews began to set up organisations for the advancement of Jewish culture.

The growth of Jewish trade and industry impeded the operations of the National Democratic party, which had a strong presence in Kielce. In 1912, slogans encouraging the residents to boycott Jewish retailers, such as “Keep to your own”, began to surface, and a portion of the city’s population started to avoid Jewish stores, handicrafts enterprises and wholesalers. Despite the offensive from the Kielce press, the boycott had little resonance with the citizens of Kielce. Jewish trade did not succumb during the boycott and new stores and wholesalers even opened. In 1914, Jews owned 276 stores in Kielce, including 85 groceries, 42 textile shops and 33 leather and shoe shops. The boycott didn’t affect the handicrafts market either.

In 1916, after the death of Rabbi Mojżesz Jerozolimski, the position of Rabbi was filled by Abela Rapoport. By then, Kielce was home to 16,000 Jews.

he situation in Kielce became very grave after Poland regained her independence. Hunger abounded, medicine was scarce, unemployment was rampant and the merchants became impoverished. The difficult times, coupled with the National Democrats’ efforts, brought about a rift between the Jewish and Polish communities. Even though the city had up to that point never experienced anti-Semitic disturbances, just a spark was enough during the tense political situation. On November 11 of 1918, an anti-Jew street riot erupted in Kielce, resulting in the deaths of 4 Jews and injuries to over one hundred. After the police investigation, several people were arrested on charges of robbery. The delicate situation between the Poles and Jews would continue for another several months, resulting in Poles avoiding Jewish stores and vice versa. However, the situation shortly returned to normal.

Despite the tension, the Jews of Kielce voiced their support for the establishment of an independent Polish nation. The Jews celebrated the anniversaries of Poland regaining her independence on November 11 and of the constitution on May 3, which was accompanied by a festive service at the Kielce synagogue. The sentiment of unity with Poland was especially pronounced after Hitler’s rise to power in Germany.

The Kielce Jews were owners of industrial plants, steelworks, timber mills and quarries, and Jewish trade had expanded even further. The already existing stores, wholesalers and warehouses solidified their positions in the economy. Jews were at the forefront of the coal, building supplies, steel and paraffin trades and owned as many as 189 grocery stores. But trade in Poland was generally small-scale, with handicrafts also suffering, and the proposition of a boycott on Jewish trade didn’t catch on among the city’s residents.

In the twenty year period between wars, the Kielce Jewish community was incredibly diverse, which was not without impact on political and social life. All of the existing organisations, from the communists to the orthodox radicals, were vying for attention. Jewish education developed and in 1918 the Jewish Denomination Middle School for boys, which enjoyed a high level of prestige, had around 200 students. The teachers of Jewish schools were very active in all of the social and cultural initiatives as well as in the Jewish community council. There were also a dozen or so private schools, of which Adolf and Stefani Wolman’s eight-class school for girls was especially popular.

The Jews of Kielce also very actively participated in municipal government through their presence in the City Council, on which members of the Jewish intellectual class had made a significant mark. In addition, Jews were involved in freelance and self-employed fields, with Jewish doctors enjoying a great level of prestige and esteem.

Jews never constituted a majority in Kielce; they accounted for about one third of the city’s population. But relations between Poles and Jews, although not without problems and occasional antagonism or reluctance resulting from the difficult living conditions, were generally acceptable.

The census of 1931 indicated that Kielce had a population of 58,236, of which 18,073 were Jews. It was a society comprised predominantly of small plant workers, petty merchants and craftsmen. For a large number of them, Kielce was just a stop on the road to a better life, which they hoped to find not only elsewhere in Poland but also abroad. Many Jews were leaving Kielce for larger cities or emigrating, chiefly for economic reasons.

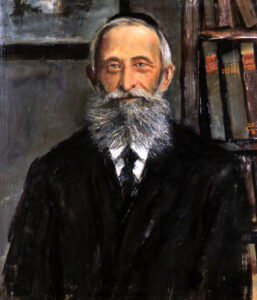

historian, journalist, director of the Center for Patriotic and Civic Thought, author of articles on the history of the Jews of Kielce.