Letters written by Hanka to her brother Aby, sister Sura and brother-in-law Hershl, exiled to the mines in Siberia, have survived, brought first from under Chelyabinsk to Poland and later taken to Israel for emigration. These letters, sent from occupied Kielce by a Jewish girl, are today also a priceless document – a testimony to the first years of the occupation, a time of steadily worsening living conditions for Kielce Jews, increasing repression, restriction of personal freedom. This testimony is all the more valuable because documents and memoirs of those who survived the Kielce ghetto have not survived much.

Their seemingly simple content is all the more striking when one realizes that the truth of the time of occupation and the cruelty of the war is hidden in them not only from German censors, but also from those closest to them, whose suffering in occupied Kielce did not want to worry additionally about their fate. Hanka writes only as much as could be written. The Goldszajd family, thrown out of their house on Focha Street, first lived on Staszica 12, and then – again thrown out, like their Jewish neighbors – found themselves in the attic of a house on Nowy Świat Street at number 15. From here letters were sent to Siberia.

God is human, man is inhuman.

– Nikolai Berdyaev, Philosophical Autobiography, 1940

Hitler will pass like a bad dream… The world will cease to be a slaughterhouse. Peace and order will be restored. And yet, many years from now a child will ask: “Mom, did they kill a man or a Jew?”.

– Maria Kann, In the Eyes of the World, 1943

It is the Nation which received the Commandment “Thou Shalt Not Kill” from God, which has in particular suffered from killing.

– John Paul II, a speech in Auschwitz, 1979

This is how after many years Moshe Meir Bahn, a survivor from the Kielce ghetto, recalls the deportation of the local Jews in four transports to Treblinka in 1942: “Before the second transport they decided to liquidate the orphanage. It held two hundred children. The house was located in the Jewish district. All the children, along with their tutor Gucia, were led to a pit in Nowy Świat Street and ordered to undress. They did not want to, therefore Gucia was commanded to make them do it. She refused. Ukrainian nationalists started beating her. The kids were weeping: “Mom, help!”. Eventually they were undressed by force. One of the Jewish policemen took them to the edge of the pit, then Rumpel started shooting them one by one with single shots. Ninety percent of those who fell into the pit were still alive. They were placed in layers, forty bodies each, and then covered with lime. In this way several layers of children and lime were stacked”

Those who survived this massacre were later killed at the bakery courtyard at the corner of Jasna and Okrzei Streets. German soldiers killed the patients in the isolation ward, pushing them out of a third floor window.

From his window at 63 Piotrkowska Street, Zygmunt Śliwiński, a local man, watched what was happening in the ghetto: “During the liquidation days I saw some gendarmes escorting about thirty pregnant women of Jewish nationality to a square near Radomska Street. They were made to kneel down and then the Nazis shot them. I was thirteen metres away”.

Another eyewitness reports: “Gestapo men commanded by Thomas were having a contest to see who would kill more people. They were aiming their pistols from the most outlandish shooting positions: over the shoulder or from between the legs. They were tipsy, but not very drunk”.

This is how Bahn, quoted above, describes the first day of the deportation: “Six thousand people were led down Młynarska Street. On both sides Poles stood, watching. The escorted Jews were followed by a few horse-driven carts and when someone, exhausted, fell or was dragging behind, they were immediately put on the carts by Jewish policemen and then shot by an SS-man.

As historian Jacek Andrzej Młynarczyk states: in the three days of the liquidation operation in the Kielce ghetto, about fifteen thousand people were sent to death at Treblinka II and about two thousand were killed as “untransportable”. Only five hundred escaped, some of them trying to join local guerrilla fighters – very few survived. Around two thousand Jews stayed in Kielce, first put in the labour camps and then sent to Auschwitz and Buchenwald among other destinations.

Jasna Street, Okrzei Street, Nowy Świat Street… Whenever I walk these streets, scenes from the past come back, those heard or read about. I remember one in particular, related by a Kielce friend who was a teenager at that time. He was going down the street on a bright, sunny day. Ahead of him a couple was walking – a tall man in a German uniform was holding an elegant young lady by the hand, a Jewess my friend knew. They were talking aloud, laughing. Suddenly, with his free hand, the man took the pistol out of his holster, put it to the woman’s head and shot her. Then he walked away, leaving the dead body in the street.

As for me, from my childhood days in Białystok I remember scenes of my fellow kids playing in the cemetery where the murdered residents of the local ghetto were buried. To this day in my mind’s eye I see skulls and shin bones scattered around in the cemetery grass and the football rolling about. The adults did not react. Neither the teachers, nor the parents, nor the priests, nor the militiamen. No one.

Well, kids needed a place to play, right? But I did not play. I do not remember what I was thinking, but I do remember my feelings: of horror and shame. Most of all I remember the pain when one day bulldozers and workmen arrived to level the cemetery in order to build a square and a real playground with swings and sandpits. That was when the Białystok menorah finally descended underground.

It was twenty years after what we call World War II. A long time or a short time? How important is time in this case? How many such “occurrences” took place in Poland? Let’s take Opatów, for example, not far from Kielce. Here the local Jewish cemetery vanished into thin air and where once stood the old ohel – a tomb of a prominent Jewish religious leader – now stands a concert shell and people walk around, go shopping, listen to folk concerts and have fun, with recent graves underfoot.

Memories from my childhood, of things that I saw and heard about, are rekindled whenever I walk the streets of the old Kielce ghetto and see the houses from those days, when I look at these few silent, inanimate witnesses to that horrible tragedy. At the same time I cannot see a single plaque, however small, to commemorate the despair, pain and suffering of those helpless, innocent victims. I do not mean we should erect monuments everywhere. Our whole land, our nation, at least very many of its sons and daughters deserve to be immortalized in stone and metal. The point is not to let the remembering die, because it is the only thing we can do – all the more so, as we could do very little then and right after. We need to find new ways to enrich our remembering and the remembering of those who will follow. Books are one of these ways. And the one you are holding in your hands is one of these books.

Marek Maciągowski: Letters from the ghetto

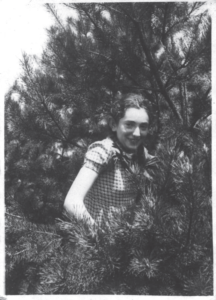

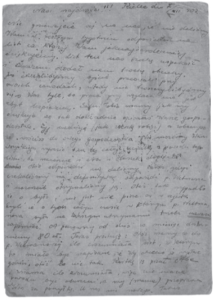

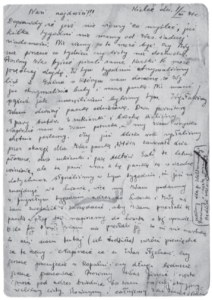

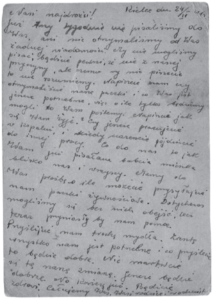

A few dozen photographs, letters and postcards are the sole material remnants of the Goldszajd family, who lived in Kielce before the storm of World War II.

Hanka Goldszajd – author of most of the letters – her mother Rywka, her father Jakub and her brother Chaim did not survive the Holocaust. Dispatched from Kielce, they all perished in Treblinka. What survived are the letters Hanka wrote to her brother Abe, sister Sura and brother-in-law Herszel, sent to a coal mine in Siberia. The letters were brought back from Chelyabinsk to Poland and preserved. Then they were “emigrated” to Israel. These letters, sent by a Jewish girl from German-occupied Kielce, are priceless historical documents, a testimony to how increasingly hard, oppressed and restricted the life of the local Jewry was. What makes them even more valuable is the fact that documents and reminiscences of Kielce ghetto survivors are a rarity today.1

The Goldszajd letters, written just before the Germans established a ghetto in Kielce, are in a way complementary to the letters of Gertrude Zeisler from Vienna, published in 1981, who wrote to her family all around the world.2 Gertrude Zeisler, an educated woman who knew Europe well, was a keen observer of the operations of the Kielce ghetto administration and of the ghetto residents.3

Unlike Gertrude Zeisler, Hanka Goldszajd was not a worldly woman. She wrote about her immediate family, about the way she lived, about how much she missed her sister and brother and how her parents tried to make a living in those hard times.

These letters are very personal, a true and direct testimony to the martyrdom of the Kielce Jews. The contents, simple at first glance, are all the more gripping when we realize that the truth about the horrors of occupation and of war atrocities is hidden between the lines not only to slip past German censors, but also to spare the relatives of those suffering in occupied Kielce from worry.

Hanka wrote only what was allowed to be written. The Goldszajds were evicted from their Focha Street home and moved to a place at 12 Staszica Street. Then they were evicted again, like all their Jewish neighbours, and made their home in the attic at 15 Nowy Świat Street. This is where the letters to Siberia were written. On the 1st of April, 1941 the house was included within the ghetto boundaries. It stands to this day, being one of the last remaining ghetto buildings.

In 1939, Hanka Goldszajd was 17. She was the youngest child of Jakub and Rywka Goldszajd. She lived with her parents and brothers Chaim and Abe and her sister Sura on Focha Street. Her father Jakub ran a transport company. He had two buses carrying people to Łódź.

The Goldszajds were one of 3,500 Jewish families which lived and worked in Kielce. At the outbreak of World War II, the Jewish community in Kielce had 20,942 people4 .

In August 1939, a sense of danger was already in the air. Alicja Birnhak recalls her return from the summer holidays: “When we were coming back to Kielce in late August, panic was already there. The roads were full of people returning home. Our childhood and adolescent days were over”.5

Hanka Goldszajd could have written the same.

Many Kielce Jews were conscripted into the army. Some of those who stayed later decided to go to the east. These people included: Josek and Leon Zajączkowski, Chaim Wajsbrot, Alicja and Henryk Strumw, Malina Kaminer, Icek, Mojżesz and Szarlota Kahan, Sara Zylbersztajn, Jurek and Pola Pelc, Icek Obarzański.6

Alicja Birnhak recalls: “Hearsay reaching Lwów from Kielce said that life over there was not that bad. Mom and Auntie were under illusion that the Germans were gentlemen, so women and children were safe there… Mom and Auntie decided to go back to Kielce, to their husbands… Mom was determined to return, but told Jurek to stay in Lwów because as a young man he could be subject to all sorts of oppression, like being sent to a forced labour camp”.7

Many Jewish families returned from Lwów to Kielce in October of 1939. Later it became more difficult to get back to Poland. Those who managed to return did not survive the war. The oppression of both Poles and Jews began immediately after the Germans entered Kielce. In October Jews between the age of 14 and 60 were pressed into forced labour. Ritual kosher practices were forbidden. On the 1st of December, 1939, all Jews were ordered to wear Star of David armbands. Beginning the 1st of January, 1940 Jews were forbidden to leave their places of residence. On the 9th of September, 1940 they were banned – punishable by fine or imprisonment – to enter the main market square (Rynek), renamed Adolf Hitler Platz. As early as September 1939 Jews were evicted from finer flats, forbidden to have cash, deprived of their property and restricted in trading foodstuffs.

The letters sent from Hanka Goldszajd to her family confirm what we know about the suffering and extermination of Kielce Jewry, even though Hanka, aware of censorship, avoids directly saying the truth, alluding to it instead between the lines. On the 31st of August, 1940 she writes: “ … we moved for the third time. Now we live at 12 Staszica Street, at the Szpirs’, as subtenants … At the moment we have no permanent address” – which means that, having been evicted a few times, they did not know whether they would be forced to move again.

14th September, 1940: “Daddy earns very little, to be frank. The two cars are still in Kielce, but we get nothing from it” – which means that the cars had been confiscated and the family lost their source of income.

25th October, 1940: “Today we’re celebrating the Sukkoth holiday. Do you know at least that it’s a holiday today? Are you having a day off or not? Dad’s working today though” – which means that her father was forced to work, whereas, as a Jew, he would not work on that day.

7th December, 1940: “Don’t worry if you don’t get a letter from us every week, we’re not sure if we’ll be able to write that often” – meaning that letter writing had become restricted.

The letters express concern for the family’s well-being. Short phrases and questions like: “How is your life over there? Do you work in your trades? Do you have a place to sleep? Do you have food? Write to the family in Wilno and America, perhaps they will help you and send a package”. Little is said about the situation in Kielce, so that the children in Siberia would not worry.

On the 21st of December, 1940 Jakub Goldszajd writes: “Dearest Children, I’m sending a set of black clothes for Abe and another black set for Herszek, only the trousers are pale, they’re mine, because we couldn’t find the right ones” – which means that clothes were no longer easy to find in Kielce. Under German occupation life was getting harder day by day, both for Poles and Jews. Because of increasing restrictions, getting food took strenuous effort. Supporting one’s own family – the foundation of Jewish life – was increasingly difficult.

At the beginning of 1941 Hanka’s letters become even sadder. She writes that it is cold outside and inside, that they had to sell the furniture…

“I’ll describe this hovel for you,” she writes, “as you can’t call it otherwise. There’s a garret, a small kitchen and a room, very low, no sunshine inside, and the worst thing is that it’s ice-cold in there, you can heat it as long as you wish to no avail. Thank God summer’s coming. I’ve never missed summer as much as I do now. In the afternoon we usually go out. Mother goes to see the neighbours, Father goes to Cuker or one of his other good brothers. Chaim goes to the shop and I stay at my friends’, because it’s cold and disagreeable here. Besides, there are only two beds in the flat, since we sold all the other furniture except for the kitchen appliances”.

A spark of hope twinkles whenever the relatives in Wilno can help a little. Shoes and grease sent to Siberia made life a bit easier for Sura, Herszel and Abe, toiling in a coal mine.

But life in Kielce is very hard. Hanka’s mother has two geese. She plucks them to have feathers for a pillow for her daughter. Hanka writes about herself and other young people: “… we’re having a good time but with a bit of blackness… We get together at their homes or mine, because we have nowhere to walk. Don’t think that I’m a kind of nun or holy person, I spend some time with my male friends as well, and we even meet at our place. Daddy and mommy don’t mind because, as I said, there’s nowhere to go for a walk”. Nevertheless the Kielce family kept sending parcels of clothing to Siberia and waiting for postcards, even though they rarely came. The children sent some food from Siberia to help their parents and siblings, even though getting food there was not easy, either. When in March of 1941 they received a package containing 2 kilos of flour, 2 kilos of semolina, 2 kilos of oatmeal, 1 kilo of kasha and 4 bars of soap, the Goldszajds wrote back: “Thank you a thousand times for it but we ask you not to send anything else. We honestly do have food and quite enough. It’s much better when you eat the food yourselves than send it to us”. They ask only for tea, “provided it’s cheap” because Jews cannot purchase tea in Kielce.

not purchase tea in Kielce. On the 31st of March, 1941, “Ordinance Establishing A Jewish Quarter Within the City of Kielce” was issued. This was the way the ghetto was called – an area where Jews were allowed to live. Nazi propaganda justified its creation as a way of protecting the Aryan population against epidemic infections supposedly spread by Jews. One of 400 created on Polish soil, the Kielce ghetto was established on the 1st of April, 1941. In fact, it consisted of two ghettos – the so called “big one”, bordered by Orla, Piotrkowska, Starozagnańska, Pocieszka and Radomska Streets, and “the small one”, between Bodzentyńska Street and Święty Wojciech Square, those two areas being connected by an overpass next to the synagogue. This district, partly surrounded by a fence and partly by barbed wire, was emptied of Poles and filled with Jews who were rounded up from around the town. Every thirty yards there were warning signs, written in Polish, German, Yiddish and Hebrew: “Area closed off. No entry”.8

Between 25,000 and 27,000 people had to occupy about 500 small houses, a few of which still stand on Nowy Świat Street. Among the local residents were Jews from Kraków, Łódź, Poznań and even a thousand from Vienna. Crowded conditions and hunger were prevalent. The Jewish Council – the Judenrat – took efforts to organize ghetto life. A hospital, a post office, an orphanage and a nursing home were established. There was even a sort of Jewish police. Jews had to work in rock quarries, timber mills, metal shops, and at loading depots. There were cheap soup kitchens. Religious practice was forbidden. By the 24th of April the Goldszajds were already living in the Jewish district. They write to their children in Siberia: “We haven’t written to you for three weeks and have had no news from you, either. However, it’s not our fault, we couldn’t write”. For the first time they ask for food: “We’d like to ask you a favour, please send us some food. Until now we’ve managed on our own, but now it would help. Send us some soap too. In fact, everything is scarce here, so whatever you send will be appreciated”.

This was the last letter sent from the Kielce ghetto. Jakub Goldszajd wrote one more card to his sister in Brazil. In it, he asked for help for his children in Siberia. The family exchanged letters and helped each other in any way they could. Sura (Sala) sent a card to Palestine, thanking her uncle Chaskiel for a parcel.

The Kielce ghetto became a place of torment. Its residents were sent to concentration and labour camps.

In 1942 the Germans made preparations to liquidate the ghettos. The summer of 1942 saw the “Reinhard” Operation put into effect. On the 19th of August, 1942, fifty cattle cars rolled into the Kielce railway station. On the next day, at 4 am, people were dragged out of their homes. Children, the elderly and the handicapped were killed on the spot, their bodies dumped into pits along the Silnica River. Three transports were sent to Treblinka. On Wednesday, the 22nd of August, 1942, children from the Jewish orphanage were shot by the river. Their teacher Gucia stayed with them until the very end. Other children were killed at the gate of the bakery on Okrzei Street and in the courtyard opposite the Church of the Holy Cross.

On the 24th of August, the Nazis murdered all the Jews in the nursing home and ordered poisoning of all the Jewish patients in the Jewish hospital. Their bodies were dumped into pits along the Silnica River.

All the Kielce Jews sent to Treblinka perished.

Survivors of the Kielce ghetto, totalling about 2,000, including 50 children and 250 women, were put in the Jasna-Stolarska camp.

The Kielce ghetto ceased to exist.

Only a small number of Kielce’s Jews survived the Holocaust – mostly those who worked in various labour camps and later, herded from one camp to another, lived to see liberation. The Jewish children of the camp were shot on the 23rd of May, 1943.

***

In one of the wedding photos we see the authors of the letters: Hanka Goldszajd with her parents Jakub and Rywka and brother Chaim, Abe Goldszajd and Herszel Kotlicki with his wife Sura. This is their last picture taken together.

We do not know exactly when Hanka, Chaim, Jakub and Rywka Goldszajd died. But their photographs and letters survived. In this way the Goldszajds regain their names among the victims of the Holocaust.

Marek Maciągowski

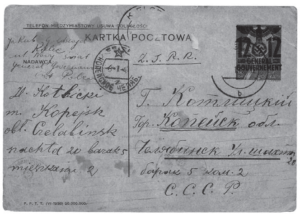

Destination:

Kopeysk,

Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

For Mr. Kotlicki, USSR

Sender’s address:

Gomel, 39 Komsomolskaya Street, door 2

USSR

Andrushenko to Mentlik

12th January 1940

I’m writing again, though there’s been no reply from you yet. Today I received a letter from our Gucia, saying that Weltman had already paid her back 200 zlotys and that she’d asked him if I should keep sending money to his wife. He said he had to pay off your father, so if you tell me that the lady needs money I’ll send it to her. So Sala, please please let me know if she needs the money and then I’ll send it to her immediately and you will also send a message home, to him.

I sent you a parcel with 4 kilos of peas, 2 kilos of groats and some soap. Please let me know when you have received it. I’ve also sent home a 10 kilo parcel. I’d love to know if they got it for sure.

Mania and Bernard

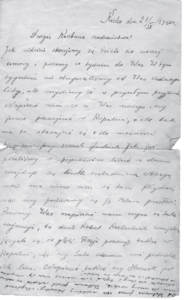

Kielce, 31st August 1940

Our Dearest Ones,

At last, after a long wait, we’ve got a postcard from you, which delights our longing hearts. There’s been no message from you for nearly three months. You can imagine how puzzled we were that you hadn’t written at all before leaving Lwów. We sent seven postcards to Lwów, alas, with no reply. Please tell us why you went to the Urals, if it was your own decision. Please tell us what it’s like over there, if you have everything you need. What kind of work do Abe and Herszek do? We’d rather they worked in their trades. How much do they earn? What kind of food do you have and what does your place look like? You write that you miss having a bed, does that mean that you have nowhere to sleep? Please write more and in detail as your card made us very happy. Write as often as possible!!! Where exactly in the Urals are you, in the north or the south? Are you happy there? “Life is nothing without work”, or “Die Arbeit macht das Leben süß”, so you should be happy.

As for us, we’re alive and in good shape, thank God. Dad earns very little. Chaim works, though wages are low, but we keep on living and hoping it won’t take a turn for the worse. As for me, I do nothing. I’d like to make myself busy, but there is nothing for me to do here. I’m a different Hania than I used to be. “Times are changing and so are we”. I’ve changed both mentally and physically. I’m bigger, more solemn. As for work, I only help Mom when she needs it, that’s all, but at the moment there’s nothing to help with, since we moved for the third time. Now we live at 12 Staszica Street, at the Szpirs’, as subtenants. We intend to move to Targowa Street (the same place where Tadek used to go with Abe). So for the time being, send the letters to Dziedzic at 6 Równa Street. At the moment we have no permanent address. You ask for photos. We’ll be happy to send them at the first opportunity, but please do the same.

As for Marjim, please, give her whatever she needs. Hilel will pay you back. You ask us to take care of your things. Please, don’t worry so much, we do whatever we can and everything’s in perfect order. No big news around here, Edzia and Sala (from Łopuszno) got married. Please tell Abe and Herszek to write back, because Herszek hasn’t written a single word since we got separated and even if he suffers from scribblophobia, he should write to us (that is to me, his brother-in-law), shouldn’t he? So, please write together. It’s been nearly a year since we got separated, amazing how fast the time goes, but we’ve gone through so much during this time. Please say if you sent letters to Chaskel. Write to Uncle Dawid and to everyone.

Well, that would be all for now. Please write as often as possible, Mom is always crying and thinking about you, in short: we miss you dearly. Your letter set her mind at ease, at least for a while, so remember to write more often and here’s the most important thing – have hope, we’ll meet again, God willing. Grandma sends her love. Helcia and Mojżesz stay at her place, they send regards, too. Gucia had typhus, but, thank Heaven, she’s well now, living in Małogoszcz with her sister, Szajndla, and she receives wonderful letters from Mirjam. That’s all for now. Best wishes, lots of kisses,

Your Mother, Father, Hancia and Chaim

P.S. Please write to Uncle Dawid and to Chaskel and to us, often. I’m not done with writing this letter yet, as Mom’s just told me to add that it’s been exactly a year since the war started. It’s Friday today. A year ago we gathered together at the Shabbat dinner. Oh, how good it was! And now… [crossed out]. It was our last dinner together. Please tell us if you still have all the things you took from home and bought from Marjim’s sister.

And tell us if you are in a labour camp or work on your own. Sorry for these confused ramblings, but it’s not easy to say goodbye even in a letter, that’s why we can’t stop. But I really need to finish now. Please write often, we shall do the same.

Kisses and with love,

Hancia

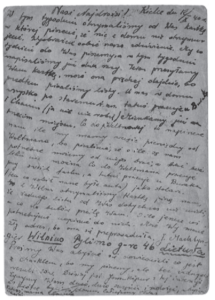

Our Dearest Ones,

We want to tell you that we’ve been receiving your letters more often now, sometimes even twice a week. We know you get anxious when there’s no news from us, but honestly, it’s not our fault, we write every week and if we could write more often, we’d surely do it. As for us, please don’t worry, we somehow manage to live day by day.

Daddy earns very little, to be frank. The two cars are still in Kielce, but we get nothing from it. Chaim earns pennies, but again, please don’t worry. Take care of yourselves, don’t deny yourselves anything. You write you live in a barracks. What’s it like? Is it a shed of some kind or what? Or maybe a sort of dwelling house? We’re so sorry Sala has no place to sleep. But what can we do about it? If we could help we’d do our best. Please tell us what your farm looks like. We hope you can find work in your respective trades. There is Abe’s craftsman card at home, we can send it to you if it would help to have it, so please let us know. We sent a letter to Aunt Ryfcia, asking her to send you some shoes. We guess she’ll do it because Grandmother wrote to her about it, too. Tell us if you have all the things you took from home and those you bought from Marjim’s sister and whether you need anything. You told us to take money from Mr. Weltman if we need any, so please tell us how much we can take. Mrs. Weltman wrote a letter home, saying: “Mr. Goldszajd’s children want to send me away”. Is it true? There’s not much to report here. Please, just don’t worry that you are so far away from home. You mustn’t get dispirited because hope is the crucial thing. Eat and drink, find good beds and get jobs in your trades. So far we’ve had no news from Chaim and we’re dying to get a word from him. We’ll send him a letter today. Please write to him, too, to find out how he is. You complain we haven’t answered all your questions. Okay, so Grandmother is well, she stays with Helcia and Mojżesz. Srulki is doing okay somehow, his youngest child was very sick but has recovered now. As for Syra Chyca, well, it’s as usual, which is bad. Mom’s asking you to keep your spirits up and write as often as possible. I’d like to ask you, Sala, to look after Abe, he’s always been a feeble boy, and now he works so hard, so how is he doing? Winter’s coming and you say it’s very cold over there, so please find yourselves some warm clothes if you can. Write a letter to Uncle Dawid, he can probably get some information on Chaskel. Finally, please do not lose hope.

With lots of love,

your Mother, Father, Sister and Brother

Dear Sala, thank you for asking about me in every letter but honestly, there’s not much I can say. I do nothing. Apparently the school will start again, so maybe I’ll be studying. Though we used to argue when you were in Kielce, you are in my heart as the most beloved sister of mine. Don’t be angry that I’m mentioning these moments of dispute, because for me they were moments of happiness, as we were together. You’re so dear to my heart. Being so far away from you, I can see what a wonderful person you are. May we meet soon, oh, how I long for it. So, take care and please think about me sometimes, the one who stays quietly in the background.

Hancia

We’re very glad you can work, but to tell the truth, we are worried to learn you work in a coal mine. We hope you can find jobs in your trades. At the beginning many people from Kielce took up jobs in coal mines inside Russia, but now they write home, saying they work in their trades, so please do try to find work in your business. As we’ve already told you we were […] forced labour, but we can manage somehow. And please do not worry that you are far from home, please do not lose hope. Do not deny yourselves anything, eat and drink and don’t worry about us, we can manage. As for your things, they’re fine, don’t worry. The time will come when you will get them back for good. They are still the same way Sala stashed them away, so there’s no need to worry. Please tell us what your place looks like, if you have any furniture and if you still have the things you bought from Marjim’s sister and that you took from home. Please write what your house looks like. Abe and Herszek, I want to ask about your jobs, how many hours is your working day? How much do you earn etc.? In short, please tell us how you’re doing over there. What’s your day like after work? Abe told us to take money from Weltman, but please specify how much we should take. You know we can’t take without limit.

Here’s the plan, and please stick to it as will we: we’ll be writing one letter a week no matter whether we receive a reply or not, because letters may get held up along the way, so please do write regularly every week. One more request: please tell us how Chaskel’s doing, because we have no news from him. If you can write to him, then please do. Also, write to Uncle Dawid. Now it’s time to say goodbye. Greetings and kisses,

Your Mother, Father, Chaim and Chancia

My Dearest Sisters and Brothers,

Thank you very much for asking about me in every letter, but there’s no news really, I am working with Witecki in my workshop. Please tell me how things are over there. I need to finish now, it’s Friday and I have to go to work.

With all my love, your brother

Chaim Goldszajd

Our Dearest Ones,

As you can see, we follow the agreement to write to you every week. This week we didn’t get any letter from you, but hopefully we’ll get something next week. Please write about any new developments. Do you still work in the coal mine? If the answer is yes, do try to find jobs in your trades. As we said in the last letter, there is Abe’s craftsman card at home, maybe it can be useful, so we’ll try to send it. Please tell us what Sala’s doing, because a lot of women from Kielce, sent into Russia, also work in coal mines. Does she work in a mine? Please write if Herszek is happy to be with Sala and how you get along together. What does Mrs. Weltman do? How is she? How much do you earn? Enough for decent living? Have you got all the things you took from home and those you bought from Mrs. Weltman’s sister? There’s not much news here, the most important thing being that we are well. Don’t worry about us, at least we are at home. Last week we wrote to Chaskel. Let us know if you’ve got any news from him. We also write to Aunt Ryfcia every week (three times so far) about the shoes, but haven’t got any answer yet. Still, we think she’ll send you the shoes anyway. Let us know if you’ve written to Uncle Dawid and Aunt Genia. Well, that’s all for now. Please, keep writing, often… Kisses and goodbye,

Your Dad, Mom, Chaim and Chancia

P.S. Please write about everything in detail.

[a note scribbled upside down on page 1]

We haven’t taken any money from Mr. Weltman yet. Please tell us

how much we should take. Mr. Weltman asks you treat his wife kindly and give her whatever she needs, if possible, and he’ll pay us back.

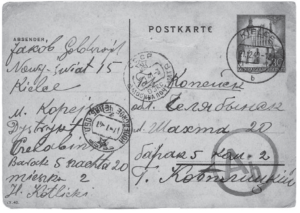

H. Kotlicki

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20-44-12, Barrack 5, Room 2

Hana Goldszajd

Kielce, 12 Staszica Street

General Government in Poland

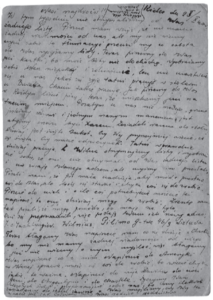

Kielce, 12th October 1940

We got a postcard from you this week, saying you haven’t received any mail from home. You can well imagine how shocked we are. We write to you every week and this very week we’ve already sent two letters. Now we’re sending a postcard, maybe it’ll go faster, since before that we sent letters. No big news here, Daddy works at Burak’s workshop and Chaim works there too (I don’t work). We moved to a new place for the third time. As for Mrs. Weltman, please tell us how much money we should take from her husband, because you said we could ask from him if necessary, but we can’t take without limit. Mr. Weltman works in his trade, but Dad works as a carpenter for Burak (the one who used to repair our cars).

We got a postcard from Wilno, saying they haven’t got any letters from you and that they’ll send you the shoes. Let them know if you need anything else.

Maybe you have a wrong address, because she moved to another place recently: J. Machtyngier, Vilnius, Pylimo g-ve 46, Lietuva. Please try to find out how Chaskel’s doing, because we keep writing but there’s been no reply. It’s Yom Kippur today, so we wish you a lot of joy and happiness and a quick return home. We kiss you all,

Dad, Mom, Chancia and Chaim

H. Kotlicki,

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

Kielce, 25th October 1940

My Dearest Ones,

This week there’s been no letter from you. You say you’ve got no news from us, which is a mystery, as we send you a letter every Saturday. From now on we’ll be sending postcards because maybe it’s just letters that are not delivered. We can well imagine how anxious and puzzled you are, but don’t worry, life is still liveable here. Daddy works for Mr. Burak in his carpentry shop, Chaim works too. As we wrote before in every letter, we moved for the third time. Apart from that there’s no news. The most important thing is that we are well and our only wish is to be always together, to be sitting around the table as we used to. Today we’re celebrating the Sukkoth holiday. Do you know at least that it’s a holiday today? Are you having a day off or not? Dad’s working today though.

We get letters from Wilno, but can you imagine, they have no news from you and they don’t know your address, so we sent it to them. They say sending you anything is hard but they’ll do their best. So write to them if you need anything, because they say they can afford to help you. They’ve moved to another place recently so I’m sending you their new address: J. Machtyngier, Vilnius, 46/9 Pilimo Street, Lietuva.

We implore you to write how Chaskel’s doing, as we’ve had no news from him and we don’t know what to think. So please, tell us how he is. Write to America about your problem, maybe they’ll be able to do something, you know how important it is. Write to Uncle Dawid, to Aunt Genia, to Argentina and to Chaskel. We wish you a happy holiday and please remember us, as we always remember you, especially when we’re sitting around the table and your seats are empty, and then we wonder whether you have enough to eat etc. Kisses,

Your parents and the whole family

Regards to Mrs. Weltman. How is she?

Kielce, 28th October 1940

Dearest Ones,

This week we received a postcard from you, thank you very much. You really have no idea how happy and enthusiastic it makes us to get letters from you. The last postcard written by Abe was dated 30th of August. We don’t know why you don’t get our letters as we keep sending one every Saturday. We hope that by now at least one of them has been delivered. We’re very happy you’re well and in good shape. Do you work very hard and what is it exactly that you do? We wish you could work in your trades, but you’re still in that coal mine, right? Please write if you’ve got beds and what kind. Do you have a decent place to live? Marjim, Gucia’s sister, writes great letters. Tell us if you have enough clothes. Did you manage to take all your things from Lwów? What does Mrs. Weltman do? We thank her for her regards and please pass our best wishes to her. We know that her husband writes to her. Tell us how much money we should ask from Mr. Weltman, because you told us to take money from him. As for Chaskel, we’ve had no news from him at all. We sent him a letter, today we’re sending another one through the Red Cross, but there’s been no answer. We keep writing to Auntie in Wilno every week about the shoes, but there’s been no answer either. But we think she’ll send you the shoes. Tell us if you need anything else. We wrote a few words to Uncle Dawid and again, there’s been no reply and we don’t know how to explain that.

There’s not much news here. Chaim works, but the wages are rather poor. Generally, we manage somehow, except for worrying about you… Do you have clothes to wear? Do you have a place to sleep? Aren’t you hungry? Have you got a place to stay? Etc. We do have a place to live, though it’s already the third one, and we have a place to sleep.

We’re surprised that Herszek hasn’t written a single word all this time. What’s up? Is he angry or something, because we truly have no idea what makes him so determined not to write. Herszek, please scribble down a few words at least, because Mother is mad at you. We’re asking you to write about everything, in detail and at length.

That’s all for now. With lots of love,

Your parents and the whole family

Dearest Ones,

Thank you very much for asking about me in your every postcard. It proves that you remember me as I remember you and hold you in fond memory, even the moments of dispute between us. Every little thing stays with me. I live by hope of meeting you again one day, of talking to you about the times we were separated. When we are back together, we won’t argue anymore, we’ll live a life of harmony. This is my plan. I hope, it’ll come true one day. As for me, I haven’t been doing anything until now, but on Sunday (tomorrow) I’m going to work, in the carpentry shop, lacquering beds. I can well imagine your surprise as you’re reading these words, but you have no idea how happy I am to have this job and how hard it was for me to get it. Quite a lot of my female friends do the same thing, even secondaryschool graduates. We can earn from 3 to 3.50 zlotys per day. The job isn’t that difficult and the most important thing is that I’ll be going to work overjoyed and singing. I’m running out of space for writing. Bye, bye for now. I’m sending you lots of kisses.

With love, Your sister Hancia

H. Kotlicki

H. Kotlicki

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

USSR

Jakub Goldszajd, Kielce, 15 Nowy Świat Street

General Government in Poland

Kielce, 23rd November 1940

We have no idea why for the last three weeks there’s been no message from you and whence this silence. Please don’t keep us waiting for too long. There’s not much news here. Chaim works. Don’t worry about us. We are in good shape, alive. We get letters from Auntie in Wilno. She’s sent a parcel recently. Nothing new apart from that. Goodbye for now,

Sending a lot of kisses

Your parents and the whole family

P.S. Please write back as soon as possible.

Goldszajd

15 Nowy Świat Street

General Government in Poland

Dear All,

Don’t be angry that we didn’t answer your letter last week. Thank you very much for it. It was somewhat reassuring and encouraging to get it. We wish you could work in your trades, then we wouldn’t have to worry so much, because working in a coal mine is very dangerous.

Sala, Mom (and we too) wants to thank you for your detailed description of the household. Have hope, as you do, and you’ll see that one day you’ll get back to your place. We can’t express the joy the letter brought us, more so as Abe and Herszek wrote at last, too. We didn’t answer promptly because we were waiting for a conclusive answer from Mr. Weltman and at last we have it. It says as follows: “let bygones be bygones”, which means that the time when Mrs. Weltman was supported by you must be forgotten. Starting from now, we will get 80 zlotys per month. Now, to clarify things: it seems that Mom misunderstood the message about Mrs. Weltman, she didn’t say you wanted to send her away, that’s not the case. The note was written by Abe and Mom got it all wrong, so you have no reason to be outraged about that and we (Mom) apologize for the misunderstanding. Nothing new here, Dad and Chaim earn a little. We are already provided for the winter. Please write what the winter’s like over there, whether you got used to it etc.

Don’t worry if you don’t get a letter from us every week, we’re not sure if we’ll be able to write that often. Regards from Grandmother and Gucia (she’s already arranged everything with Mr. Weltman). Bye for now and we’re waiting for a quick and long answer. Kisses for all of you,

Don’t worry if you don’t get a letter from us every week, we’re not sure if we’ll be able to write that often. Regards from Grandmother and Gucia (she’s already arranged everything with Mr. Weltman). Bye for now and we’re waiting for a quick and long answer. Kisses for all of you,

Your parents and the whole family

Kielce, 15th December 1940

Dear Children,

This week we received a letter from you, thank you a thousand times for that. Again, we want to tell you it’s a holiday for us, when we get a letter from you. We write to you nearly every week. Believe us, we’d like to write more often but we can’t. Abe and Sala, surely you’re angry with your Daddy that he doesn’t write but you see he tried and stopped because it’s hard for him to express himself. You ask why we lost our flat at Staszica Street, well, as you know we now live at Nowy Świat Street. You know, the Zwiklers, the Rapsztajns and the Szpirs do not live there anymore, either. Chaim works in the workshop, Daddy has some work with Burak from time to time. Do not worry about us, we manage somehow. We are safe from hunger and cold. Take good care of yourselves. Please try to get out of that mine and find work in your trades. As for Dziedzic and Konstanciak, here’s how things stand: Dziedzic sometimes acknowledges that Jankiel, the Jew exists, but Konstanciuk doesn’t want to remember about his relations with Daddy, doesn’t want to hear about the debt, either. Everything’s been said. Now about Mr. Weltman: we would like to do it as follows: Mrs. Weltman pays you for your support and she can get the money from Marjim, Gucia’s sister, and then Mr. Weltman pays the money back to Gucia. We think it’s the best solution. So far we’ve received 190 zlotys from Mr. Weltman.

Dear children, I’m very sorry that my sister still hasn’t sent you the shoes. She wrote to me to send her the birth certificate, because then she would be able to send you the shoes, I’ve already sent it. Please write to her. I’ll send you a parcel by post. I need to finish now, my best wishes, do not worry about us.

Your father Jakób Goldszajd

Mother sends her love and she hopes to hear from you as soon and as often as possible

Dear Abe! Thank you very much for your postscript in the letter. However I don’t understand why you lament so much about my going to work. Work is my motto now. The times when I was afraid of being seen carrying a big parcel across the street are long gone. Oh, how silly I was. I’ve changed. The words “child”, “my little sister” made me laugh; of course, I was loved, but that’s another thing.

Don’t think you’d see the same Chancia as before, no way. Those childhood days are gone for good. Now I’m a serious person. Not so skinny anymore. If I tell people who didn’t know me before the war that I was a skinny girl, they laugh it off as nonsense. Today I am fat (as Sala used to be), solemn and tall. I will try to send you a photo. You write that I should take care of our parents’ health, that they are ill. I know that very well. You don’t have to remind me at all. I help Mommy as much as possible and I’ll try to follow your advice. I often try to guess what you look like in the mine but it’s hard for me to imagine you with coal. I really can’t help it.

That’s all for now, I’m sending you a thousand kisses.

With love, thinking about you all the time,

your sister, Chancia

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

H. Kotlicki

Jakób Goldszajd

15 Nowy Świat Street, Kielce

Kielce, December 1940

I’m sending a set of black clothes for Abe and another black set for Herszek, only the trousers are pale, they’re mine, because we couldn’t find the right ones. When you get the parcel please let us know what else we should send you. Wishing you good health,

Your father J. Goldszajd

Kielce, January 1941

Our Dearest Ones,

We’re very surprised we haven’t received any news from you for three weeks, but we’re writing to you anyway. We’re not going to do the same in return because we’re sure it’s not your fault. Last week we wrote a postcard to you, saying that Weltman doesn’t deliver what he promised, that is he doesn’t pay us regularly, but you know your Daddy, he is so emotional and acts without thinking. You’ll be surprised to hear that Weltman gave us 100 zlotys this week, which makes 370 zlotys in total. Don’t be angry that we say different things every week, but God forbid, if I don’t write what Daddy wants, you can well imagine all the shouting, you know your Daddy well, you know how quick-tempered he is. Not much to report here, everything is much the same. The only problem is that winter has hit us hard, and everyone else as well, for that matter. Hard frost and snow storms. We’re thinking about you all the time, your situation is surely more difficult. Please write whether you are not freezing and whether you have enough clothes to wear, because though we’re cold, we’re at home. Two weeks ago we sent you a parcel with two suits. Please write us if you got it and if you need anything (nonsense – surely you do!). So please write and we’ll send whatever is needed because we don’t know what you want. For example, when we sent you the suits, we’d already collected a parcel with warm underclothing for you and then the letter came, saying you needed some suits. We think it will be summer again, by the time the letter reaches you and you write back. We’re extremely happy and grateful to you that we have some news from our brother. If possible, please send us some words from him. Write us if you work in your trades. You have no idea how much we’d love to learn that you got out of that hole.

Please write if there are hard frosts and how Herszek is doing and if he still has rheumatism.

Please write about everything and in detail, because you can’t imagine how we’d love to know how you’re doing and how life is over there. I’m confused, I keep writing, though I feel it doesn’t make much sense. However I’d like to write you about everything and it’s so difficult for me to be away from you. Writing gives me this sense of being with you, though only in my head. I’m always with you,

I promise. Now when you’re so far away, I can see clearly how precious and dear you were to me while you were still at home (despite our little arguments), and even more now, when you are so far away. Sala, I need to write a few more words to you. Imagine that Niusia Jabłońska will be getting married one of these days. Oh yes, I forgot to say that I’m attaching a note from Helcia Rapsztajn. She asks you to write to her husband, who doesn’t write to her at all, so she doesn’t know how he’s doing. Mommy asks you to do it for her and to forget the past, this woman is really desperate. She has a ten-month-old child – such a cute thing. Mommy and Daddy are talking about it all the time. In general, they are on friendly terms with the Rapsztajns. They pay us visits. Chaim and Daddy go to them too. So again, please find her husband if you can. You have no idea how important it is for her. It’s time to finish now, because there’s no more room to write.

Lots of kisses,

Your parents and the whole family

[Letter from Helcia Rapsztajn-Bergman]

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

H. Kotlicki

H. Kotlicki

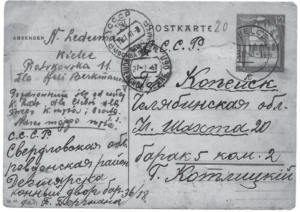

N. Lederman, 11 Piotrkowska Street, Kielce

For Hela Berkman

Kielce, 26th December 1940

Dear Sala,

You’re probably surprised by this letter, but because I haven’t received any news from my beloved husband, who is in the Urals too, I’m writing to ask you to be so kind and write to him, to ask if he is in good health and tell him to write to me because I have no news from him at all. This makes me – and my whole beloved family – very sad. We don’t know what to think about it.

ery sad. We don’t know what to think about it. So, my beloved Sala, please get in touch with him and tell him that you’re my cousin. Ask him to write back whether he is in good shape and how he is doing, because I and my whole family are in despair. Believe me, the best cure for all my pain is my beautiful and lovely daughter, whom I love so much. I implore God to let the baby be hugged in her father’s arms. Sala, I know that you’re such a generous person and you’ll do it for me, so I thank you in advance. I’m waiting impatiently for your kind and quick, if possible, reply. Write how you’re doing over there. To tell the truth, we’re hungry for every bit of information from all of you and as a result your beloved relatives pass everything on to us.

We wish you good luck. Sending lots of kisses.

Helcia

Lots of love from Ruchcia.

I’m sending best wishes from my whole beloved family to you, your beloved husband and brother. My husband’s address: USSR, Svierdlovsk Oblast, Rievidienskaya Region, Konnyi Dvor, Barrack 36/18

For F. Bergman

Deutsche Post Osten

USSR, Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

For H. Kotlicki

[Added] Rybak

Dearest Ones,

We don’t know what to think, as we haven’t gotten any news from you for more than four weeks. You can imagine how we’re feeling. We’re asking you to please write as often as possible. We keep writing to you every week. This week we got a few letters from Wilno. They say they received a letter from you, saying that you needed shoes and some grease. They said that they’d be able to send you a parcel every month and that they had already sent you 8 kilos of grease. In two weeks they’ll send you the shoes, because they’re still waiting for a permit to do it. The shoes are ready for dispatch. Hanka’s married an engineer and they’re leaving Wilno for Japan because there’s an assistance committee called “Joined”, and then from Japan they’ll go to America. Please write whether you received any parcels from Wilno. As for Weltman, we told you last week that he’d already given us 410 zlotys and now he pays us 80 zlotys a month. In total, so far we’ve received 410 zlotys. There’s not much at home to report. The winter is hard for us, we’re very cold. How about you? Do you have any warm clothes, as obviously it’s freezing over there? Please, let us know if you received those two suits and if you need anything. Love for you and regards for Mrs. Weltman. How is she doing? Sala, do you get letters from Marjim, Gucia’s sister? Because she gets mail from you very often.

Kielce, 1st February 1941

Our Dearest Ones!!!

Finally, after six weeks a long awaited letter arrived. You can imagine how concerned we were by this prolonged silence, but we have the letter at last.

From it we found out that you hadn’t received our successive letters saying that we received 420 zlotys from Weltman. He gives us 80 zlotys a month. We were surprised beyond words, reading that “Marjim’s sister could have had 50 zlotys per month for the flat”. It was laughable and painful at the same time to read it. Willy-nilly, I’ll describe this hovel for you, as you can’t call it otherwise. There’s a garret, a small kitchen and a room, very low, no sunshine inside, and the worst thing is that it’s ice-cold in there, you can heat it as long as you wish to no avail. Thank God summer’s coming. I’ve never missed summer as much as I do now. In the afternoon we usually go out. Mother goes to see the neighbours, Father goes to Cuker or one of his other good brothers. Chaim goes to the shop and I stay at my friends’, because it’s cold and disagreeable here. Besides, there are only two beds in the flat, since we sold all the other furniture except for the kitchen appliances. She (Marjim’s sister) keeps her furniture here and we have to look after it. Now you know what kind of flat we have, but please don’t worry and although we hate moving, as you know, we’ll surely move to a new place as soon as we find a clean, decent flat in this district. Abe, you shouldn’t get annoyed about Weltman, he’s been paying us 80 zlotys every month fairly regularly, but we thank you for remembering and helping us, even though you live in such dire conditions and work so hard. Hopefully, we’ll be able to repay you one day.

Sala, Marjim’s sister misinformed you about the feathers, so let me put this straight: Mother still has two geese, she didn’t sell them. She tears the feathers off and puts them into your bedding

Even today (when it’s warm) she’s tearing feathers off in her spare time and thinking about all of you and we’re looking forward to meeting you again. Daddy doesn’t work, I’ve already told you what he does, he visits friends or harasses us. He’s very, very nervous. Please, don’t mention in your letters what I’m saying about him, that he argues with us (in fact, with me and mother), because I’d surely have to flee from home, as he’d be angry at me. So again, please, don’t mention it to him. Apart from that everything’s the same here, only we’re thinking about you all the time.

Dear Sala, thank you very much for writing a few words, you have no idea how happy I was to receive this letter. You say that all you’ve gone through has braced you up. As for me, though it’s easier here, life has taught me a lot as well. As for my private life, it’s not that bad. After all you know that we young folks don’t like to worry too much. Cheerfulness is our motto, so we’re having a good time but with a bit of blackness, especially me, because I miss my nearest and dearest. Oh, how painful is this yearning! I also help Mother, but she has less work than before.

Now, as for my friends (I don’t know, maybe you are tired of hearing), I spend time with Lusia, you remember her, I suppose, and with Sala Gold, whose family has a big outfitter’s shop, and with Rózia Mandelkiern, the one who is such a graceful ice skater. We get together at their homes or mine, because we have nowhere to walk. Don’t think that I’m a kind of nun or holy person, I spend some time with my male friends as well, and we even meet at our place. Daddy and mommy don’t mind because, as I said, there’s nowhere to go for a walk

Oh, I’ve been boring you long enough, haven’t I? There’s nothing new apart from that. Time ticks by so fast as usual. God willing, we’ll meet one day, I keep thinking about it all the time. I think about you in the daytime, but at night it’s almost like I’m with you. I dream about your return. Tell Herszek that I’ve visited Srulek several times already, but he’s too busy to write even a few words. He is exactly like he used to be. Enia’s grown a little bit and she’s a fine girl now, perhaps a bit too talkative. She speaks German nicely but only some words. No news about grandmother. Aunt Helcia and Mojsze are still together. Mojsze sold his furniture too. I’m (we’re) very surprised that you received neither the letter, nor the parcel from Wilno. They wrote us that they had sent you some money and a parcel with eight kilos of grease. We sent you a parcel of clothes. I guess you should have received it by now. Imagine that Hanka from Wilno already got married! Stupidity conquers everything! That must be all for now, thousands of kisses,

Please pass my regards and kisses to my beloved brother-in-law.

P.S. Special greetings from my friends. They often remember you as my pretty sister and Herszek as my handsome brother-in-law.

Hello, my beloved Abuś!!!

And I thank you too for your postscript. Reading it, I thought you were teasing me for my seriousness. But don’t think I’m going to feel offended or let myself be bossed around. You should know that I’m sharp-tongued, but this time I’m not going to show you how talented I am in this respect. By the way of explanation I’ll just pinch some cash for a photo and send it to you and then you’ll see that you’re dealing with a somebody (seriousness aside!). You can learn about me from the letter to Sala. You ask about your friend Baranowski (a stone of a man, frankly speaking, if he hasn’t written to you all this time.) So far this fellow has bothered to send only one postcard home. And do you know why? Because he found out that parcels could be sent from here to you over there. So at the moment he is in Krzemieniec and apart from that I have no news about him. Let me tell you before I forget: Miss Hela is sending you and Sala best wishes. I meet her very often because my friend Lusia lives together with Rozenholc, so I go there, and Hela works there, so I meet her, whether I like it or not. Apart from that there’s little news. That’s all for now. I’m sending lots of kisses.

Loving you always,

Hanka

[note at the top, scribbled upside down]

Kindest regards from my friend Lusia (do you remember her?), the one who went with me to the Czerwona Mountain. She remembers you as a good brother of mine and regrets she doesn’t have one like you.

Wilno, 6th February 1941

Dear Salcia,

Firstly, I’d like to thank you for your congratulations on my engagement.

Here are details about me and my husband. On 21st of December, 1940 I and my husband got registered, intending to go to Japan in a few weeks’ time. We had no idea we wouldn’t be able to go together, but it transpired that I couldn’t go with him. As a refugee having an entry visa, he can go to Japan, whereas I, though being his wife, but having no visa, can’t go with him. So he needs to go alone and upon arrival he’ll try to get a visa for me. So he’s going now and I’m staying. My dearest Salcia, you know how it is, because your loving husband went away at some point and you stayed at your parents’, just as I am doing now. And in the same way you hoped you’d meet again and you did, so I’m hoping we will meet again in Japan or at Chaskel’s place (because he’ll probably go to him) and be happy. I thank you so much for wishing us happiness together. You ask what my husband does. My beloved husband is a bookkeeper but he hasn’t worked recently because he was busy planning the journey. He’s a quite handsome, goodlooking boy, as you’ll see in the photo which I’ll send in my next letter. I gave out all the photos I had, so I ordered more – they are being made – and when they are ready, I’ll send you some at once.

I think that’s all I can tell you about myself and my husband. I suppose you’ll be surprised by that thing with your cousin, but it’s not our fault.

My dear Salcia, please write in detail how you’re doing. Since Abe sent us a pretty long letter, we know everything about him and Herszek. But he wrote little about you, so please let us know how life is over there, what you do, where you go, if you have any friends etc. I hope you’ll oblige me. Bye for now, I guess I’ve bored you enough. Give your husband and Abe my regards. I’m kissing you many times from afar, with love, Hanka. Kindest regards from my husband. I suppose you’re surprised he didn’t answer your letter, but he’s not home. He’s gone to Kowno.

Hanka

Deutche Post Osten

USSR, Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

H. Kotlicki

J. Goldszajd, Kielce

15 Nowy Świat Street

Kielce, 15th February 1941

We’ve been receiving your letters only occasionally. We don’t know why. Do you write as often as we said before, that is every week? Or maybe your letters get lost? Anyway, we want you to write more often because it’s so hard to wait for any news from you. We write to you every week no matter whether you answer or not. There’s not much news here. We’re alive and in good shape. Chaim has a new business partner in the workshop. It’s an ex-journeyman of Mr. Lederman, his name is Mydło. He seems to know his trade all right, we’ll see how it goes, because he’s been in the shop only a few days. Chaim is satisfied with him. Mr. Witecki works too. We got a letter from Aunt Gucia. She didn’t write anything important. There’s been no mail from Wilno recently. We’ve received 510 zlotys from Weltman. Please let us know if you got the parcel with clothes, the one we sent a long time ago. That’s all for now. We’re sending lots of kisses and please do write more often.

Let us know when you quit working in the coal mine.

Let us know when you quit working in the coal mine.

Good-bye!

,

Hana

Deutsche Post Osten

USSR, Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

H. Kotlicki

J. Goldszajd, Kielce

15 Nowy Świat Street

Kielce, 1 III 1941

My Dearest Ones,

We really don’t know what to think. We haven’t got any news from you for a few weeks now. We have no idea how you’re doing. Maybe you don’t write every week or your letters get lost? Please send postcards instead, they probably go faster. This week we got a letter from Wilno, saying that you received the shoes and our parcel. You have no idea how happy we were to learn it. We sent you a parcel today: two suits, three pairs of shoes, three dresses and some underwear. Please write what you need and we’ll be happy to send it. It’s been nearly a year since we had the chance to send you a parcel containing two cloaks, two dresses and a pair of shoes, Sala’s cherry-red summer ones.  The parcel was sent via a woman. She’s still travelling with it. We heard this week that the parcel is in Lwów at the moment, so just ask them to send it to you. We’ll send them a message about it too. Don’t worry if you don’t get it because in this case their family will pay us back. Please write how you’re doing, whether you still work in the coal mine and how long you’ll be working there. Write as often as possible. Perhaps it’s better to send the letters to Mr. Dziedzic, as the mail seems to come more often to his address. Bye for now. We kiss you all.

The parcel was sent via a woman. She’s still travelling with it. We heard this week that the parcel is in Lwów at the moment, so just ask them to send it to you. We’ll send them a message about it too. Don’t worry if you don’t get it because in this case their family will pay us back. Please write how you’re doing, whether you still work in the coal mine and how long you’ll be working there. Write as often as possible. Perhaps it’s better to send the letters to Mr. Dziedzic, as the mail seems to come more often to his address. Bye for now. We kiss you all.

Your parents and the whole family

Regards to Mrs. Weltman. Write often. Stay healthy.

Wilno, 2nd March 1941

Dear Salcia,

It was a joy for me to read your letter. I’m so grateful for your trying to comfort me in these sad times. You ask me when my husband is leaving. He’s leaving Kowno in three or four days, which means on the 5th or 6th of March. I’m going to Kowno tomorrow to say farewell to him. It looks like he’s not going to Japan, as I told you in my letters, but straight to Chaskel, and I’m very happy about it. Salcia, I understand your situation and I feel very sorry for you. I can imagine, based upon your description, how stylish your apartment is.

Don’t worry, God will help you and you’ll all be reunited with your parents. Everything can be restored, the apartment as well. I just visited your place and was impressed by it. Dear Salcia, that’s all for now. Kind regards to your husband and Abe. I kiss you all.

Hanka

P.S. I’m sending you some photos of my husband and me. He looks intimidating, but he’s not really like this.

Hanka

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

H. Kotlicki, USSR

Kielce, 7th March 1941

Dearest Children,

We got a postcard from you this week. What’s going on over there? We haven’t received a letter from you for six weeks now. We sent you a parcel, but there’s been no word whether you received it or not. Mrs. Weltman wrote a letter to her husband, informing him that she’d received a parcel, but there’s no message from you though we sent ours only three days later than Mr. Weltman did. My sister in Wilno says she got a letter from you, saying that you’d received a parcel of clothes from home. The package my sister writes about was sent on the 27th of February and weighed 9 kilos. It contained clothes, dresses and summer shoes. Please write every week, preferably postcards, as they go faster, as for letters, please write them the way I’ve written this one: first, the address – the same one that’s on the envelope – then we’ll get them for sure. Dear children, please write what we should send you, maybe summer coats, a quilt or a pillow.

Abe, please write if you need those shoes we keep at home. You said you sent a food parcel, thank you very much for it, but we ask you not to do it again, save for yourselves what you want to send to us. We don’t need anything, as we have plenty of food here and we can afford it because Chaim earns quite well in the shop, and I do the same, making some money. Moreover, Weltman gives us 25 zlotys a week now plus we get some cash from Konstanciak, so don’t worry. We ask you once more: don’t send food parcels and don’t deny yourselves anything. If you earn any money, please spend it on food and eat well. If tea’s not too expensive over there, please send us some and some sugar cubes. Dearest children, I sent a parcel to you in June 1940, via a daughter-in-law of Fiszel Zilberberg, known as Fiszel Gozdek, the owner of the clothes shop in which Chaim works. He has a son in Lwów, his name’s Aron and Aron’s wife was in Kielce with their child. Aron Zilberberg sent documents from Lwów to his wife and I gave them a car for free so she could go to Krakow with her luggage. She took along two white summer coats for you, two dresses for Sala and Sala’s shoes. But to this day I haven’t had any news about these things. Fiszel warranted that if it got lost, he’d pay us back. Here’s his address: Lviv, Aron Zilberberg, N36 Y. Kopernika Street, USSR. When she (Aron’s wife) went there, were you still living in Lwów? Send him a letter and let me know if you get a reply. That’s all for now. We wish you all the best, regards from us all,

Your parents Goldszajds, who love you very much.

Why doesn’t Herszel write something? Is he angry?

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

H. Kotlicki

J. Goldszajd, Kielce, 15 Nowy Świat Street

General Government in Poland

Kielce, 15th March 1941

Thank you very much for the postcard written by Abe and dated 25th of February. We received a food parcel as well, containing 2 kilos of flour, 2 kilos of semolina, 2 kilos of oatmeal, 1 kilo of kasha and 4 bars of soap. Thank you a thousand times for it but we ask you not to send anything else. We honestly do have food and quite enough. It’s much better when you eat the food yourselves than send it to us. Abe writes in the postcard: “Tomorrow we’re sending a food parcel”. Does that mean it’s another one? If that’s the case, again, we ask you not to send anything except for tea, provided it’s cheap and it’s not a problem. But only if it’s cheap and the mail charges are low enough, otherwise do not send it.

Two weeks ago we sent you a 10-kilo parcel of clothes. We have no confirmation from you that you got the first parcel but we were told about it in a letter from Wilno. Your letters don’t come, only postcards, so please send postcards as often as you can. In the last letter Daddy gave you Mr. Zilberberg’s address, the one who lives in Lwów and has your parcel, taken by his wife nearly a year ago. Contact him and ask him to forward it to you. We’re sending him a letter about it. His address: Aron Zilberberg, Lviv, 36 Kopernika Street, USSR.

Please give our regards to Mrs. Weltman. How is she doing? Sala, please let us know if you get letters from Marjim, Gucia’s sister, as she receives letters from you pretty often.

Not much to report here. We’re in good shape. Yesterday it was Purim. Everything would be fine, if we were not separated. God willing, we’ll be celebrating the holiday together next year. We kiss you all,

Your parents and the rest of the family

R. Goldszajd, Kielce, Radom District

Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast

Coal mine 20, Barrack 5, Room 2

H. Kotlicki

Kielce, 24th April 1941

We haven’t written to you for three weeks and have had no news from you, either. However, it’s not our fault, we couldn’t write, but we have no idea why you don’t write anymore. Please let us know if you got the parcels and need anything, we’ll send it if we can. Write how you’re doing. Do you still work in the coal mine? When will you finally look for a different kind of work? As for us, I’ve already told you that Grandma lives close by, the others as well. We’d like to ask you a favour, please send us some food. Until now we’ve managed on our own, but now it would help. Send us some soap too. In fact, everything is scarce here, so whatever you send will be appreciated. But please don’t worry that our situation has deteriorated. We’ll bounce back soon. Time to finish now. Stay healthy. We kiss you all,

Your parents and the whole family

Your parents and the whole family

Sala! Gucia got a letter from Mania, saying she’d sent 150 roubles to Goldfarb’s daughter. Write back if she got the money and tell her to send a letter home and another one to us, otherwise Mr. Goldfarb from Kielce won’t honour the debt.

Geni Handerbock

Au Augusto Severo 38 I, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Jakób Goldszajd, 15 Nowy Świat Street, Kielce

General Government in Poland

Kielce, 8th March 1941

Dear Sister,

I received your letter. Thank you for it and for remembering your brothers and parents in Kielce. I’ve had no news from our brother Szlama, nor from Dawid, though I’ve sent him a few letters. Mother hasn’t got anything from him, either. Perhaps you could write to him. Don’t worry about us, we’re in good shape. Mom and Moszek are well too. But my son Abe and my daughter Sala are in Siberia. I can give you their address: USSR, Kopeysk, Chelyabinsk Oblast, Mine 20, Barrack 5, room 2, H. Kotlicki.

They work in a coalmine, dear sister, so if you’re able to help them, please do and ask Dawid not to forget about them.

Warm regards to you, your husband and children. We wish you all the best,

Your brother J. Goldszajd

I have Chaim, Chancia and my wife at home with me. Stay heathy.

If you’re going to write me a letter, please write the same address that’s on the envelope on page one, then the mail will be delivered for sure. It should be done the following way: on top you put my address and then the letter follows.

Palestine, Tel Aviv, Renak 12

A. Rozenwald

TSSR [Tajikistan], G. Leninabad, Ozodi 100

H. Kotlicki

Leninabad, 23rd July 1944

Dear Chaskiel,

Dear Chaskiel, This week I received a parcel from you, for which I’m very grateful. I got a bath towel, bloomers, a women’s suit, a pair of socks and 3 bars of soap. Many thanks. Abe sent you a postcard last week. We also sent a letter and a telegram to M. Kotlicki. We’ve sent many letters to him and dispatched a telegram, but there’s been no reply. Well, he can’t be cross with us. Getting a letter is a great holiday here, that’s why we write so many of them. Chaskiel, send us Dawid Kotlicki’s address, we’d like to write to him too. We sent a few cards to Wilno. You should send some mail there, as well, perhaps we’d learn something. How are you? Your letters make us very happy. You write that you manage and live quite well – we’re very glad to hear it.

There’s no news here. Abe and Herszek work as usual and earn quite good money. I feel much better now that I’ve gotten somewhat used to the climate.

That is all for now. I kiss you many times,

Your loving sister Sala

Herszek and Abe send kisses from afar. Regards to all our family and friends and best regards to Mrs. Zosia.

[brak daty i nagłówka]

[…] we’ve got nothing else from Weltman. Gucia asks if you could write where her sister Szajndla is, because she has no news from her. I sent you Marjim’s address in another letter, but I’m resending it just in case: Klipiki Raz, Krasnyi Sveysk Oblast, for Berko Mentlik.

We ask you to try and find out about Chaskel. We’ll try to get Minyl Kotlicki’s address for you. As for Srulek, he manages somehow, thank God, but it’s a very hard time for him. The little child (not Enia) has been sick recently. Grandma is well and the same in general. As for the shoes from Wilno, they’ll try to send them to you along with some food parcels.

We write them a postcard every week. They haven’t received your letter, so please write to them once more. Here’s their address again:

Machtyngier, Vilnius, Pilimo Street 46/9, Lithuania

Sala, you asked about Basia Borensztajn – she’s dead. She died on Sukkoth Eve. I think that it will be all from me now. Take good care of yourselves and don’t worry. Good-bye, thousand kisses from us,

Your parents, brothers and sisters

P.S. Please write as often as possible. Give Mrs. Weltman our

kindest regards, how is she?

Hanka

[excerpt without date or signature, page 2].

My dearest Sala, I wanted to write to you several times but my mind is always preoccupied. I can tell you I’ve been through a lot since you went away. I got typhus and I had my hair cut. I was bald as a coot, but now it’s grown a bit and for Easter I’ll again have another crop of hair on my head. Forget it, no use dwelling on it, what’s gone is gone, there are different worries now. You ask if I work, well, I do, but very little. Auntie doesn’t work either, she makes a living selling her old linen and getting whatever Ryfcia sends from Wilno. Imagine that your grandma doesn’t go out at all, she does nothing except for cooking. She cries all the time, because she hasn’t received any letters from Dawid.

[list bez daty i nagłówka]

At last I can tell you that Chaim got a license in his name and he’s independent. Witecki doesn’t work there anymore, he left with no hard feelings and now there’s perfect order in there, as it becomes a barber shop. If you have with you my yellow sandals, please send them to me if you don’t need them and it’s not a problem. As for Weltman, everything’s fine now, he’ll be paying 25 zlotys a week. Let Mrs. Weltman add something in with your letter.

Dears, you don’t have to worry about us, everything’s all right. Your husband earns his living, looks well and he will do whatever he can to help you. Don’t worry that you’re far away from home. That’s how life is, there are many cases when the husbands stay in Poland and the wives are in Russia, or the parents are in Poland and the children are in Russia. Stay well and stick together, and when you earn money, spend it on food. Take good care of yourselves. We wish you good health and all the very best,

Your loving mother and father Goldszajd

Greetings from Chancia, Chaim, Grandma and Uncle Moszek with

his wife

I need to add a few words. We have no idea why but recently the mail from you has been very irregular. Sometimes there are six week breaks. You say in the postcard that you sent us a food parcel. We haven’t received it (but hopefully it’ll come soon). Please don’t send parcels anymore. It makes no sense for you to sell things in order to send us parcels. It makes us happy when you’re well fed. We got a food parcel from Wilno 3 weeks ago, but we wrote to them that it would be better to send the parcels to you, as we manage somehow. Please write how long you’re going to stay in the mine. Is it a temporary or a permanent job? We hear forced labour duty lasts for just one year, then people can take up other jobs. Please write if it’s true or not. Again, we ask you not to send any parcels, but do send us some tea, if it’s not a problem and is not too expensive. There’s Purim this week. We wish you a lot of fun and please don’t forget about us, as we think about you all the time. I kiss you all,

Hanka

Dear Herszek,

At last you had the courage to scribble me a line. You have no idea how happy I was when I got your mail. You ask why I don’t write to you. I don’t understand it – I’ve written several times but have never received any answer. There’s not much news here. I don’t go to school, just loaf about. I go over to grandma’s and back because I have nothing else to do. You ask me to visit Srulek. Well, we paid him many visits, but he always says he’s busy. He’s in good shape, he has a job and the kids are well too. Enia has grown a bit, she’s a smart girl. Talkative and brisk. She eats everything. This week I’m visiting him, so I’ll give him your card, maybe he’ll write back. He doesn’t ask about you as often as you ask about him.

Please write me how you’re doing. How is life? What does Sala do? Here it’s all the same. Time’s passing and we sit by the stove because it’s cold. Bye for now and please write back. With love

your beloved sister-in-law Chancia

Dear Beloved Sala,